A blog about music. Interviews, concert flyers, vinyl record covers and labels, liner notes ...

Thursday 16 July 2015

Charley Patton - A Brief Biography - John Fahey

Practically all of the information presented here has been supplied by Mr Gayle Dean Wardlow of Meridian, Mississippi, Mr David Evans of Los Angeles, and Mr Bernard Klatzko of New York. However, a preliminary statement is necessary regarding the status of biographical research dealing with Patton.

In the first place, no one sought to unearth any of the facts of Patton's life until 1958, when the author first visited Clarksdale and Greenwood, Mississippi, although Patton had died 24 years earlier. No one recalled anything about Patton except that he was a great musician and songster, indeed the most popular blues-singer living in the Yazoo Basin during the last 20 years of his life. People remembered that he drank a lot and ‘lived a rough life’ (i.e. he was not very religious), and that his last record was There Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down, which he recorded a few days before he was stabbed to death or poisoned by a jealous woman. The first two of these 'facts' which many Delta Negroes ‘remember’ appear to be true. The third is easily disproved and the fourth is only half true.

In the intervening 24 years between the time of his death and 1958, practically everything about Patton had been forgotten by those who knew him best. Even his last 'wife', Bertha Lee Pate (now Bertha Lee Joiner) today seems to remember little more than that he played the guitar.

There exists a great deal of confusion about the circumstances of Patton's birth, not only among those who knew him, but among those who claim to be related to him. The procedure used in order to determine the facts is for the most part the following.

The testimony of people who volunteer information on other matters, with which the author is already well acquainted (who made the best selling record of Shake 'Em On Down; where Skip James learned his songs; what James's real name was; who Henry Stuckey was, etc.), informants who readily admit that they know nothing about a certain subject, or that they have forgotten; such testimony is given more credence than that of informants who attempt to gloss over their lack of knowledge. Consequently, much reliance is placed upon Sam Chatmon, since he has an excellent memory and seems to be entirely honest. Son House, while honest, does not possess a uniformly accurate memory, but readily admits when he is confused. Finally, I have derived information from numerous people who were acquainted with Patton at different stages during his life - people who were reliable on other matters - but people too numerous too mention.

Sam Chatmon, who provided much of the information on Charley Patton's early life and career, was a member of a large family of brothers, among them Bo, Lonnie, Harry, Sam and an adopted brother Walter Jacobs, otherwise called Walter Vincent. The Chatmon family was most prodigious in its recording career. Bo Chatmon, under the name ‘Bo Carter’, recorded more than a hundred sides for various companies. He was also a member of the Mississippi Sheiks, a group usually consisting of a vocalist with guitar and violin or guitar and piano accompaniment. The Sheiks made nearly as many records as Bo Chatmon did on his own, and most of them were very good sellers. They also recorded as the Chatman Brothers, the Mississippi Blacksnakes and the Mississippi Mud Steppers, and at one session accompanied Texas Alexander, who, in terms of record sales, was one of the top ten blues vocalists during the period before World War II. (Not much is known of him except that Sam ‘Lightnin'’ Hopkins claims him as a ‘cousin’ on occasion). Lonnie and Sam Chatmon were the ‘Chatman Brothers’ on Bluebird. Dixon and Godrich's report of this session is misleading; where there are two guitars, rather than violin and guitar, the second guitarist is Eugene Powell. Bo Chatmon acted as agent for Powell, who is still living in Greenville, Mississippi, and was once known as ‘Sonny Boy Nelson’. It was under this pseudonym that his own Bluebird records were issued, though, curiously enough, Powell was until recently unaware of the fact.

Sam Chatmon - who played guitar with the Sheiks - in retrospect regards Patton as a fairly good musician, when he was not clowning around, but feels that the Sheiks and Charlie McCoy were much more proficient, versatile and talented. The Chatman brothers' recordings are characterised by group sessions, complex chords, more use of the major 4 and major 5 chords in the same song - in general, a more sophisticated sound than that of Patton and his musical generation.

The Sheiks, like Patton, played at parties for white people, and this for a while served as their main source of income. Lonnie both read and wrote music, having learned from another black musician, who in turn had learned from an Italian violin-maker. While Bo played the violin a little, Lonnie always played it at parties and for recording sessions, since he was very much more proficient on the instrument than was Bo.

Chatmon's main criticism of Patton and the older generation was that they only knew how to play in the key of E and in ‘Spanish’ (open G). Many people have long suspected that the open G guitar tuning was derived from a very common open G banjo tuning. This may be the case ultimately, but Sam Chatmon never saw a banjo until he was in his thirties.

According to Sam ‘there was an older style around than what me and Lonnie and Bo played. Now my father he played the fiddle - old songs like Turkey in the Straw and such. My older brothers and half-brothers, including Charley played mostly in E and ‘Spanish’ and that was all! Even a couple of my older sisters played the same way. Now I can't exactly do it, but I'll show you how Charley used to come around and twirl the guitar - you, see, like this, and then play and make it come out right [sings and plays first verse of Pony Blues]. Then he had a way of tapping on the guitar too, the same time he played [demonstrates this] ... and a lot of others too, like behind his neck [another demonstration].’

Charley Patton was the son of Henderson Chatmon (father of the Chatmons and a former slave) and Anney Patton (wife of Bill Patton) and was born near Edwards, probably in Bolton, Mississippi, in the late I880s. Since Henderson Chatmon was born of a mixed union, and had very little black blood, Charley was evidently of primarily white and Indian descent. Charley had numerous brothers and half brothers by both Henderson and Anney Patton. According to Sam, morals were much relaxed in those days. His father had many ‘outside women’ and nobody seemed to mind. Charley spent about half his early life with the Chatmons; this explains some of the confusion surrounding these years.

Other people who knew Patton in and around his adolescent home on Dockery's Plantation give a different picture of Patton's family. His ‘father’, presumably Bill Patton, was apparently a part-time preacher. Patton then, had a second set of other, different relatives and siblings. His siblings by Henderson Chatmon were William and James (both deceased) and nine sisters, plus Sam Lonnie and Bo Chatmon, the younger Chatmon generation. Two of his sisters, Kattie and Viola are still alive. Unfortunately they are unreliable informants.

Charley struck out from the Bolton area in his late teens or early twenties and played in many roadhouses along Highway 80. It was during this period that he made his home, when he was home, with the Pattons. But it should be remembered that his very distinctive singing and playing style came from growing up with the elder Chatmon brothers, and, presumably, their friends. Where these styles came from, if anywhere other than around the Chatmon household, cannot be ascertained. As Sam Chatmon said, ‘Charley was a grown man when I was just a child and he was already doing all those things.’

Charley married young. His first common-law wife was named Gertrude. In 1908 at about the age of 21, he married his second wife, Millie Toy, from Boyle, Mississippi.

In 1912 a veritable congregation of guitar players and singers was to be found in and about a small town, Drew, Mississippi. The town is situated near two large plantations which were owned at the time by Will Dockery and Jim Yeagers. Patton was living at Dockery's at this time. Among the resident musicians whose presence in the area in 1912 has been confirmed (in each case by interview, then by checking with one or more of the others who were supposed to be there) were Patton, Willie Brown and his wife - who also played, Tommy Johnson, his brother LeDell, LeDell's wife Marry Bell Johnson, Roebuck Staples of the famous gospel singing family ‘The Staples Singers’, ‘Howlin' Wolf’ (real name Chester Burnett, who admits to having taken lessons from Patton, and still imitates his vocal style, unsuccessfully), Dick Bankston, ‘Cap’ Holmes and a few others who evidently travelled through the area from time to time but whose presence cannot be confirmed due to contradictory information.

According to Sam Chatmon, Patton already played and sang ‘just like’ the older brothers and sisters of the Chatmon family before he came anywhere near Drew. And since Patton seems to have left Drew still singing and playing in much the same way as before, it may be supposed that he was a major, if not the major influence on the Drew scene. Undoubtedly he left with more than he had come with - such atypical Patton songs as Frankie And Albert and Some These Days I'll Be Gone, for instance - but it seems probable that Tommy Johnson, Willie Brown and others learned much more from Patton than he did from them; this has been admitted by Howlin' Wolf and Roebuck Staples. Some confusion exists as to who learned what from whom, in the case of Tommy Johnson, since Patton's first home was very near Crystal Springs, where Johnson was born. For example, both men recorded versions of Pony Blues, for the same company, less than a year apart. Both played in open G, ‘Spanish tuning’; and not only did they both use the same tune contour - which might have been expected - but Johnson in his treatment (Paramount 13000, Black Mare Blues), used virtually the same tune phrases as Patton employed on Pony Blues. Both men used to clown; Patton danced round his guitar, Johnson round and on his Gibson. On the other hand, Patton never recorded anything in the standard tuning, key of D; and this was a tuning much favoured by Tommy Johnson, as well as by other musicians who played round Jackson a good deal, such as Tommy McClennan, the Bullfrog Blues Man. There are certain songs and verse complexes which are associated with the key of D, such as those found in the many variants of Big Road Blues - which Sam Chatmon recorded with the Sheiks, under the title of Stop And Listen Blues. The significance of all these musicians living in the same area at the same time lies in three facts. First, there was a great deal of communal creation. Secondly, after these people left Drew, the songs, lyrics, styles and so forth, which they had learned and created there, began to appear in the north (as far as Chicago and Detroit, up to the present time) and the rest of the south. They may still be recovered by any field worker virtually anywhere in the United States where there are performing, non-professional black musicians - even in the western states. (This claim takes no account of instances where the singer has learned the song from a phonograph record, even though some folklorists consider records as merely an extension of the 'normal' person-to-person diffusion process.) Thirdly, these songs, styles and lyrics became known as 'blues' even though performances, and recordings of performances, by city groups had previously been and continued to be called 'blues'. The 'city blues' were generally performed by groups, with quite 'regular' metric structure and textual coherence. These evidently newer 'country blues' were more individual (and perhaps more personal), irregular and textually incoherent or ambivalent.

Certain differences in performance can be described between those singers who went north and those who remained south, but the similarities are much greater. If field recordings and commercially issued phonograph records from the north contain more vocal growling and are delivered more harshly than those from the south, if very few examples from the north exhibit guitar-playing in the key of D while those from the south do, then source-analysis usually indicates that in the north many singers learned their songs and styles, directly or indirectly, from, say, Patton, while those in the south learned theirs from Tommy Johnson.

Musicians from the north were also, to a great extent, influenced by the Son House, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters group; those in the south by singers from Bentonia, Mississippi - Skip James and his friends - another instance of communal creation.

In many cases, after 1940, and even before that, source analysis indicates that singers learned their songs directly from phonograph records by Patton, Johnson or others. This, I think, represents a gradual breakdown in oral tradition. To attempt to represent the process of learning how to play a song directly from a phonograph record as merely an extension of oral tradition is ludicrous. To attempt to put forth definitive distinctions between a northern and a southern style of singing with the meagre information we have (meagre in comparison with what we need to do so, and could have, had more research been done at least before I940), information gained primarily from phonograph records issued after 1940, would at this late date be ill-advised.

A few years after Patton's arrival, a black soldier returned from the war in Europe and shot a white man in, or near, Drew. Other musicians had already moved, but this event really began the Drew diaspora. Most of the blacks in the area were forced to move.

Brown, Staples and his family, and Howlin' Wolf left and went north, carrying their music with them. Wolf still sings many Patton songs and Roebuck Staples plays like Patton and Brown. The Johnsons moved to the Jackson area; Tommy recorded for both Victor and Paramount a few years later, in 1928 and 1930 respectively, and stayed in Crystal Springs until his death in the 'fifties.

Patton and Johnson appear, in retrospect, to have been more imitated than innovative; more cooperative than creative. Yet few people realise that Patton was part of a large exchange process which went on for several years before his emergence as a prodigious recording star and purveyor of local songs. While Tommy Johnson remained in, or for the most part near Jackson, Patton travelled around a great deal, but chiefly within the confines of the 'Delta'.

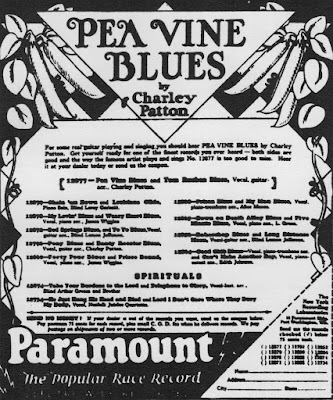

Patton later stayed at Dockery's until 1924, at which time he left and in Merigold met Minnie Franklin, whom he 'married'. This woman is still alive. Her full name is Minnie Franklin Washington, and she lives in Bovina, Mississippi. She reports that Patton was singing Pony Blues when she met him in 1924, but the song was probably much older. In Merigold, Patton became acquainted with two sheriffs, Mr Day and Tom Rushen, and a Mr Halloway who made whisky. Patton composed a song about these people called Tom Rushen Blues which he later recorded for Paramount, and High Sheriff Blues which he recorded in New York at his last session in 1934. Patton left Merigold in about 1929 (alone) and met Mr Henry C. Spiers of Jackson, Mississippi. Spiers owned a music store in Jackson, and had acted for years as a talent scout for several large record companies. He sent Patton to the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana, where on 14 June Patton had his first session for the Paramount Company. (Paramount frequently used the Gennett studios.) Patton spent his remaining years performing in the Yazoo Delta in various towns, usually near the Mississippi River, in Mississippi and Arkansas. He rarely left this area to perform.

Patton probably met Bertha Lee Pate (whom he 'married') in Lula, Mississippi, and Henry Sims (a fiddle player from Farrell) in 1929, shortly after his first recording session. He is reported by Son House to have lived and performed at Lula and at most of the local towns, especially on the plantation of Mr Joe Kirby, where he performed with Son House and Willie Brown. He also lived near there on the plantation of a Mr Geffery. He recorded again for Paramount at the company's own studios in Grafton, Wisconsin, in November and December of 1929, taking Henry Sims with him.

He began acting as subsidiary talent scout for Spiers shortly after his first two records were issued. It was through Patton that Willie Brown and Son House were recorded. In May 1930 he went to Grafton with House, Willie Brown, Louise Johnson (who sang blues and played the piano) and Wheeler Ford of the famous 'Delta Big Four' gospel quartet. Patton's final Paramount session took place on 28 May. According to Son House, Paramount used two microphones, one for voice and one for instrument. Skip James said the same thing except that when he played the piano, the recording engineer also put a microphone on his feet. The artists were well 'lickered up' before recordings were made.

Shortly after this, Patton and Bertha Lee lived for a while in Cleveland, Mississippi. It was here that Bertha Lee is reported to have had a fight with Patton and to have cut his throat with a butcher's knife. She, of course, will not discuss the matter, but the story is well known in Cleveland. That Patton survived, but with a scar on his throat, and, nevertheless, stayed with Bertha Lee is well established.

In 1933, Patton and Bertha Lee moved to Holly Ridge, where they performed locally together. Patton was suffering greatly at this time, and prior to it, from a heart ailment of which he was soon to die. He was chronically out of breath and it would take him two or three days to recuperate from a night's singing.

In early January of 1934 an 'A&R man', Mr W. R. Calaway of the American Record Company (ARC) went to Jackson in search of Patton. A&R stands for 'Artists and Repertoire'. A&R men work for record companies and music publishers; they select artists for certain songs which they want to get recorded and help supervise the recording sessions. W. R. Calaway performed both functions with such white, 'country' entertainers as Roy Acuff, Bill and Cliff Carlisle, and others. With Patton and Bertha Lee, he probably performed only the latter function. Calaway later tried to get Willie Brown and Son House to record for him, both of whom refused for different reasons. He wanted to take Patton to New York to record for his company. He contacted Spiers and asked him for Patton's address, but Spiers refused to give it to him, because, he claims, Calaway had swindled him in a previous business deal. (Spiers recalls this vividly. Unfortunately, Calaway could not be consulted, since he died in Orlando, Florida in about 1955.) Spiers notwithstanding, Calaway found Patton and Bertha Lee in Belzoni, Mississippi. During the evening of the day Calaway arrived, Patton, Lee, and others were jailed because of a commotion that had occurred in the roadhouse in which they were playing. Mr Purvis, the 'High Sheriff' of Humphreys County, and Mr Webb, his deputy, were the local law-enforcement officers. Calaway later bailed out Patton and Bertha Lee and the three left together for New York. Patton sings about both law-enforcement officers on High Sheriff Blues. Patton's (and Bertha Lee's) last recording session took place on 30 and 31 January, and I February 1934. At this session Patton sang as the last verse of his 34 Blues:

It may bring sorrow, Lord, and it may bring tears, (twice)

Oh, Lord, oh, Lord, let me see your brand new year.

He never did. The ailment which had bothered him for years was to put an end to his life. Shortly after he returned to Holly Ridge from his ARC session, he became ill. He was taken to a hospital in Indianola, Mississippi, on 17 April 1934, released 20 April, and died 28 April. Mississippi State Board of Health Certificate of Death Number 6643 attributes the cause of Patton's death to 'Mitral Valve heart hose' (heart failure).

When fully grown, Patton was quite short, about 5 ft 6 inches tall, and of lean build. He had light skin and Caucasian features. He is reported to have played practically everywhere in the Yazoo Basin and to have travelled with medicine shows. During many performances, as stated, Patton did tricks with his guitar, such as dancing around it, banging on it while he played, and playing it behind his head. He taught Howlin' Wolf, Willie Brown, and Son House a great deal on the guitar.

As distinct from such travelling performers as Blind Lemon, Blind Blake, Lonnie Johnson, and others, Patton spent almost his entire life in or near his native Mississippi Delta. He left it rarely to perform, and only a few times to make records. His recorded repertoire reflects his limited picture of the world. When he does mention place names, such places are usually located in the Yazoo Basin. Here is a list of place names Patton mentions, with the corresponding master numbers:

15220 Memphis, Minglewood (in Memphis).

15221 Pea Vine (name for either any branch line of a railroad or in this case the branch line of the Southern Railroad, which ran from Clarksdale through Shelby, Merigold and other small towns, to Greenville).

15223 Parchman (the Mississippi county farm for Negroes).

L-44 Marion, Arkansas and the Green River. (The Green River is not on any map but is a local name for a small river in the Delta near Dubs.) The Southern Railroad and the 'Yellow Dog' Railroad, a local name for the Yazoo Delta Railroad.

15214 Natchez, Jackson.

L-432 Clarksdale, Sunflower; Helena, Arkansas.

15223 Hot Springs, Arkansas.

L-37 Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana (occur as part of a refrain, probably traditional).

L-38 New Orleans (occurs in a verse of a traditional blues-ballad).

L-41 Louisiana.

L-59 Sumner, Greenville, Leland, Rosedale, Vicksburg, Stovall, Tallahatchie River, Jackson; Blytheville, Arkansas.

L-63 Gulf of Mexico; Vicksburg; Louisiana; Shelby, Illinois (not on any map).

L-77 Chicago.

L-429 Lula.

14725 Belzoni.

14727 Vicksburg, Lula, Natchez, Greenville.

14747 Mississippi, Dago Hill (a local name for the region north of Mound Bayou, Mississippi: a great many Italians live there).

Only the following people are mentioned:

15222 Tom Rushen, Hollaway, Mr Day.

14725 Mr Purvis, Mr Webb.

14739 Hollaway, Will Dockery.

14757 Bertha Lee.

No person of more than local prominence is ever mentioned and no one from outside the state of Mississippi is mentioned. When Patton sings of external events, he usually refers to local ones: the 1927 flood of the Mississippi River (Paramount 12909, High Water Everywhere - Parts I and 2), the drought of the following two years and how it was felt in Lula (Paramount 13070, Dry Well Blues), the demise of the Clarksdale Mill (Paramount 13014, Moon Going Down). The one exception is his description of the 'Railroad strike in Chicago' (Paramount 12953, Mean Black Moan).

Patton was dependent upon, and a product of, the prevailing socio-economic conditions of the southern cotton production economy, a semi-feudal society. According to Son House, Sam Chatmon and others, he detested and avoided manual labour and spent most of his adult years as a semi-professional, paid (or kept) entertainer. There was room in this economy for a few full-time professional entertainers, and although the entertainer did not earn a sumptuous living, he made a decent one relative to the standards of the time and place. If he was supported by numerous roadhouses and corn-liquor salesmen, these roadhouses and bootleggers in turn were dependent upon the (sometimes) wealthy plantation owners. Most Delta blacks worked for the plantation owners and were paid but meagre monetary wages. There was a great deal of restriction of personal freedom, and many blacks led lives similar to those of medieval serfs. Everything was white-owned and the law of the land was white law.

On the other hand, blacks who worked on Delta plantations were always provided with housing (called 'quarters') and frequently with food. When the depression came and there was no work, the black workers were fed by the plantation owners, protected by the benevolent southern land-owner tradition. There were few jobs in the Delta for blacks that did not deal with cotton, and they could not rise to a very prominent position even among their own people. A black man could become a preacher, but the best he could do in secular life was become an overseer (the leader of a cotton crew) or a musician.

If we search Patton's lyrics for words expressive of profound sentiments directly caused by this particular cotton-economy, or for words expressing a desire to transcend this way of life, if we search for verses of great cultural significance depicting any historical trend or movement, or aspirations to 'improve the lot of a people', we search in vain. Such a search would not be fruitful with any blues-singers. Patton could, of course, only sing about his own limited experience. He had a very narrow view of the world. And there was perhaps no intellectual climate available to Patton for the development of significant thoughts or comments about his and his people's status.

Patton was an entertainer, not a social prophet in any sense. He had no profound message and was probably not very observant of the troubles of his own people. He was not a 'noble savage'. Least of all did he try to express the 'aspirations of a folk'. His lyrics are totally devoid of any protesting sentiments attacking the social or racial status quo. In fact, according to Son House, Patton had very good relations with white people, many of whom helped to support him in return for his services. They liked not only his folksongs but also his blues. Both Patton and House were frequently received into white homes, slept in them, and ate in them. The racial segregation of Patton's day was not as rigorous as it is now, and it was not as insidious.

Beyond mentioning place names, Patton's lyrics have nothing distinctively regional about them that could have made them products of only a particular time and place. They could have been produced by any songster from any agricultural-economy region of the South. Most of his lyrics, or portions of them, are probably floating verses derived from field-hollers and other sources. As such they could have been performed or recombined, as they were, by anyone familiar with the tradition. It is impossible to determine exactly where and when such verses were composed, as it is impossible to reconstruct an authoritative history of black music in general. No one was interested enough at the time to survey what was happening.

As has been implied, the function which Charley Patton performed in his society was, for the most part, that of an entertainer. His function as a musician was subordinate. Patton used his musical abilities, as well as his ability to dance and to do tricks with the guitar, in order to please an audience.

We cannot know, of course, what Patton did when he was alone. Perhaps, while entertaining himself (assuming that he did so), he concentrated more on his musicianship. But as star performer of a medicine show, as the source of music for a dance, as roadhouse entertainer, as paid background music for back-country gatherings whenever local corn-liquor salesmen set up shop, Patton's job was to help everyone to enjoy himself.

Son House and Ishmon Bracey both commented on Patton's clowning. House did not approve of it and is to this day critical of Patton. As a result, when some of Patton's recordings were played for House in 1965, he was amazed at Patton's technical proficiency. 'I never knew he could play that good', he said. He then explained that while Patton was apparently a great musician, the purely musical aspect of his public performances suffered as a result of his 'clowning around', which House insists Patton preferred to do.

The apparent selectivity of House's memory seems strange in view of the fact that House was present while Patton made some of the same records which were played for him 35 years later. But House had simply forgotten that Patton was a competent musician because he saw him so frequently as an entertainer and so rarely as a serious musician. Vocal and instrumental proficiency were necessary for an entertainer, but they were not enough. Patton had the other talents as well. What we hear, then, on Patton's records is apparently not the way Patton sounded in public. On records we hear him consciously trying to be a good musician. But we should not make too much of the probable differences of performance in the two situations. Patton could not have suddenly summoned up so much technical proficiency at the recording sessions if he did not already possess it. Thus, there were probably other times when Patton performed primarily as a serious musician. Unfortunately, no one remembers such times. Perhaps he performed seriously only when he was alone. If Patton's recordings are of Patton at his musical best and do not sound exactly as he sounded at public performances, there is no reason to suppose that what he played (music and text) varied in the two situations. Thus, it seems safe to conclude that Patton's recordings constitute a valuable and accurate sample of what Patton was playing and singing during the last years of his life and probably for many of his earlier years. It should be remembered, for example, that he was performing some version of his Pony Blues as early as 1924, five years before his first recording session.

Excerpt: Charley Patton by John Fahey

Published: 1970

Publisher: Studio Vista

Country: UK

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)