This compact disc is much better than the Greatest Hits CD from 1990. Though this 1985 release is lower in volume the mix of Manic Monday is the hit you heard on the radio. The vocals are forward in this mix whereas on the Greatest Hits there is a sense that the vocals are competing for attention with the other instruments. You will hear complaints that this 1985 compact disc is too low in volume but that was normal at a time when everyone would have had a home stereo with an amplifier and floor standing speakers. Using VLC as a player you can turn this CD up or even better buy an audio interface for your computer and use the audio interface volume knob.

A blog about music. Interviews, concert flyers, vinyl record covers and labels, liner notes ...

Wednesday, 28 December 2022

Monday, 26 December 2022

Thin Lizzy - Lizzy Killers - 1994 Compact Disc

I was trawling through my compact disc collection and have decided to start adding recommended compact discs. These are compact discs that I feel do justice to the music. Hopefully this will prove useful for collectors.

The first compact disc is Lizzy Killers by Thin Lizzy. This was originally released in 1983 but the disc I have is the reissue from 1994.

Wednesday, 2 September 2015

Paco de Lucia - Wigmore Hall - 15th February 1976

Perhaps it would not be amiss to recall his first London concert at the Wigmore Hall, Friday 15 February 1976.

The foyer of the Wigmore Hall was full of guitarists mingling with aficionados in a hum of humanity, before filling the auditorium where they settled down to await the slightly late entrance of the almost unannounced debut recital of today's young king of flamenco - Paco de Lucia.

He came on, holding his Conde Esteso 'Black Flamenco' (rosewood back and sides instead of cypress), sat down, crossed his right leg over his left and in an unsmiling, casual manner (holding his guitar as most of us do when we are playing to ourselves), began with a melodic introduction which eventually led into an Algerias in the minor before developing into the major key. The tempo was easy but some of the runs were taken at lightning double speed which shot up the temperature of the performance although not of the duende. This was no ordinary run-of-the-mill flamenco style. If you have based your flamenco on Sabicas, forget it. Everything about this style is different as evidenced by the Tarantas which followed.

The traditional trills and legatos were there, very clearly defined but in a different level, played with a finesse and freedom that should have been highly charged with emotion but somehow weren't; perhaps the mask-like expression of the player with eyes shut did not help. There was no helpful programme nor did the soloist announce the titles of his offerings, the next of which was a Guajira which, as everything else he played, was recognisable by its strong compas or beat.

The variations and the rhythm sailed along freely, incorporating some popularly recognisable melodies like Leonard Bernsteins's America (West Side Story) and Canarios.

Then, changing the cejilla from the 1st to the 2nd fret, he went into an exciting and somewhat original Bulerias. Paco de Lucia certainly does not play traditional flamenco; perhaps it is an offshoot of flamenco, but whatever it is, it is played with complete mastery, abandon and freedom and makes some of the older masters sound very square. And yet is does not emit the deep emotion and great excitement of Niño Ricardo - the founder of this school.

Paco has the great gift of playing a clear melody so that the rhythm accompaniment is perfectly balanced, even to the interpolation of Falla's Miller's Dance.

For his fifth offering, he returned the cejilla to the 1st fret, and gave an outstanding rendering of a Medio Granadina in which he showed his artistry by relegating the accompanying arpeggios to their rightful position and balance, thereby allowing the melody to ride freely and clearly. Then, to my surprise, he 'rasgueadoed' into the old Panaderos Flamencos note for note like the 25 year old record of Vincente Gomez but a few notes faster, and I must say it was nice to hear one of the first flamenco pieces I had ever transcribed and played, but, I may add, with fireworks!

The second half began with a Rondena in very Moorish mood and developed with many sweeps and flourishes but with no great attempt at any dynamics. When he grabs a chord he grabs it, and when he plays a double speed run it is like a supersonic dive bomber, relentless until the bottom is reached.

The Zapateado which followed was a perfect exhibition of the triplet form of dance. If only a fleet-footed dancer could have made it a perfect duet.

One cannot say that the Soleares which followed illustrated what its name traditionally means. There was nothing lonely or forlorn about it, but a search for the new, although some of the falsetas were recognisable and well used. The Soleares changed to a faster tempo and finished with a flourish of alzapua - fascinating thumb work.

Again a change of compas, this time to a Fandango which was played excellently and in perfect tempo. He was then joined by his brother Ramon de Algeciras, who seemed to bring out Paco's lighter nature and actually produced some reserved smiles. He should do this more often!

His brother's guitar (also a Conde Esteso) was made of Palo Rosa (a lighter type of Brazilian rosewood used for strictly non-classical work) and Ramon played effectively and lightly, well versed in his job of accompanying - in this instance a guajira followed by a high speed rhumba flamenco which allowed the lead guitar a free rein to extemporise on the chords. Pyrotechnics without limit. After one of his phenomenal extra long single note passages, some of the audience spontaneously rose to their feet galvanised into action, and by this time the atmosphere had built up to great excitement.

The two guitars were brilliant in the Bulerias, the first encore, and although Paco had suffered some nail injuries during the evening's playing, he ended with another encore, a Verdiales, which interpolated Lecuona's Andalusia and Malaguena with the regular cadenzas. Although one can say that Paco de Lucia's tone production is at one level, and there is little finesse of emotional depth, he must be recognised as one who plays guitar with freedom from inhibition and with a complete mastery of technique. One of the 'Greats'.

For those who wish to know more about him, he was born Sanchez Francisco Gomez in Algeciras, the port town next to Gibraltar and opposite Tangiers in North Africa. The date was 2 December 1947 and he, his father and brothers all either play or sing flamenco.

Paco de Lucia seems to have made a relentless bee-line for solo performance rather than playing in groups for singers and dancers. I wonder if Sabicas's statement holds good when he says 'One should play with singers and dancers for 25 years before embarking on a solo career'.

Excerpt: My Fifty Fretting Years by Ivor Mairants

Published: 1980

Publisher: Ashley Mark Publishing

Country: UK

Thursday, 16 July 2015

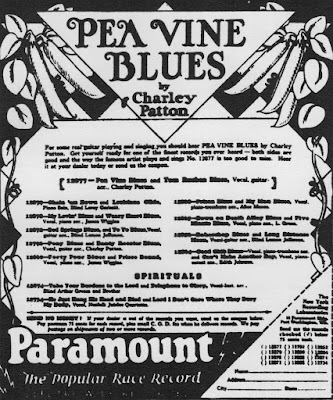

Charley Patton - A Brief Biography - John Fahey

Practically all of the information presented here has been supplied by Mr Gayle Dean Wardlow of Meridian, Mississippi, Mr David Evans of Los Angeles, and Mr Bernard Klatzko of New York. However, a preliminary statement is necessary regarding the status of biographical research dealing with Patton.

In the first place, no one sought to unearth any of the facts of Patton's life until 1958, when the author first visited Clarksdale and Greenwood, Mississippi, although Patton had died 24 years earlier. No one recalled anything about Patton except that he was a great musician and songster, indeed the most popular blues-singer living in the Yazoo Basin during the last 20 years of his life. People remembered that he drank a lot and ‘lived a rough life’ (i.e. he was not very religious), and that his last record was There Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down, which he recorded a few days before he was stabbed to death or poisoned by a jealous woman. The first two of these 'facts' which many Delta Negroes ‘remember’ appear to be true. The third is easily disproved and the fourth is only half true.

In the intervening 24 years between the time of his death and 1958, practically everything about Patton had been forgotten by those who knew him best. Even his last 'wife', Bertha Lee Pate (now Bertha Lee Joiner) today seems to remember little more than that he played the guitar.

There exists a great deal of confusion about the circumstances of Patton's birth, not only among those who knew him, but among those who claim to be related to him. The procedure used in order to determine the facts is for the most part the following.

The testimony of people who volunteer information on other matters, with which the author is already well acquainted (who made the best selling record of Shake 'Em On Down; where Skip James learned his songs; what James's real name was; who Henry Stuckey was, etc.), informants who readily admit that they know nothing about a certain subject, or that they have forgotten; such testimony is given more credence than that of informants who attempt to gloss over their lack of knowledge. Consequently, much reliance is placed upon Sam Chatmon, since he has an excellent memory and seems to be entirely honest. Son House, while honest, does not possess a uniformly accurate memory, but readily admits when he is confused. Finally, I have derived information from numerous people who were acquainted with Patton at different stages during his life - people who were reliable on other matters - but people too numerous too mention.

Sam Chatmon, who provided much of the information on Charley Patton's early life and career, was a member of a large family of brothers, among them Bo, Lonnie, Harry, Sam and an adopted brother Walter Jacobs, otherwise called Walter Vincent. The Chatmon family was most prodigious in its recording career. Bo Chatmon, under the name ‘Bo Carter’, recorded more than a hundred sides for various companies. He was also a member of the Mississippi Sheiks, a group usually consisting of a vocalist with guitar and violin or guitar and piano accompaniment. The Sheiks made nearly as many records as Bo Chatmon did on his own, and most of them were very good sellers. They also recorded as the Chatman Brothers, the Mississippi Blacksnakes and the Mississippi Mud Steppers, and at one session accompanied Texas Alexander, who, in terms of record sales, was one of the top ten blues vocalists during the period before World War II. (Not much is known of him except that Sam ‘Lightnin'’ Hopkins claims him as a ‘cousin’ on occasion). Lonnie and Sam Chatmon were the ‘Chatman Brothers’ on Bluebird. Dixon and Godrich's report of this session is misleading; where there are two guitars, rather than violin and guitar, the second guitarist is Eugene Powell. Bo Chatmon acted as agent for Powell, who is still living in Greenville, Mississippi, and was once known as ‘Sonny Boy Nelson’. It was under this pseudonym that his own Bluebird records were issued, though, curiously enough, Powell was until recently unaware of the fact.

Sam Chatmon - who played guitar with the Sheiks - in retrospect regards Patton as a fairly good musician, when he was not clowning around, but feels that the Sheiks and Charlie McCoy were much more proficient, versatile and talented. The Chatman brothers' recordings are characterised by group sessions, complex chords, more use of the major 4 and major 5 chords in the same song - in general, a more sophisticated sound than that of Patton and his musical generation.

The Sheiks, like Patton, played at parties for white people, and this for a while served as their main source of income. Lonnie both read and wrote music, having learned from another black musician, who in turn had learned from an Italian violin-maker. While Bo played the violin a little, Lonnie always played it at parties and for recording sessions, since he was very much more proficient on the instrument than was Bo.

Chatmon's main criticism of Patton and the older generation was that they only knew how to play in the key of E and in ‘Spanish’ (open G). Many people have long suspected that the open G guitar tuning was derived from a very common open G banjo tuning. This may be the case ultimately, but Sam Chatmon never saw a banjo until he was in his thirties.

According to Sam ‘there was an older style around than what me and Lonnie and Bo played. Now my father he played the fiddle - old songs like Turkey in the Straw and such. My older brothers and half-brothers, including Charley played mostly in E and ‘Spanish’ and that was all! Even a couple of my older sisters played the same way. Now I can't exactly do it, but I'll show you how Charley used to come around and twirl the guitar - you, see, like this, and then play and make it come out right [sings and plays first verse of Pony Blues]. Then he had a way of tapping on the guitar too, the same time he played [demonstrates this] ... and a lot of others too, like behind his neck [another demonstration].’

Charley Patton was the son of Henderson Chatmon (father of the Chatmons and a former slave) and Anney Patton (wife of Bill Patton) and was born near Edwards, probably in Bolton, Mississippi, in the late I880s. Since Henderson Chatmon was born of a mixed union, and had very little black blood, Charley was evidently of primarily white and Indian descent. Charley had numerous brothers and half brothers by both Henderson and Anney Patton. According to Sam, morals were much relaxed in those days. His father had many ‘outside women’ and nobody seemed to mind. Charley spent about half his early life with the Chatmons; this explains some of the confusion surrounding these years.

Other people who knew Patton in and around his adolescent home on Dockery's Plantation give a different picture of Patton's family. His ‘father’, presumably Bill Patton, was apparently a part-time preacher. Patton then, had a second set of other, different relatives and siblings. His siblings by Henderson Chatmon were William and James (both deceased) and nine sisters, plus Sam Lonnie and Bo Chatmon, the younger Chatmon generation. Two of his sisters, Kattie and Viola are still alive. Unfortunately they are unreliable informants.

Charley struck out from the Bolton area in his late teens or early twenties and played in many roadhouses along Highway 80. It was during this period that he made his home, when he was home, with the Pattons. But it should be remembered that his very distinctive singing and playing style came from growing up with the elder Chatmon brothers, and, presumably, their friends. Where these styles came from, if anywhere other than around the Chatmon household, cannot be ascertained. As Sam Chatmon said, ‘Charley was a grown man when I was just a child and he was already doing all those things.’

Charley married young. His first common-law wife was named Gertrude. In 1908 at about the age of 21, he married his second wife, Millie Toy, from Boyle, Mississippi.

In 1912 a veritable congregation of guitar players and singers was to be found in and about a small town, Drew, Mississippi. The town is situated near two large plantations which were owned at the time by Will Dockery and Jim Yeagers. Patton was living at Dockery's at this time. Among the resident musicians whose presence in the area in 1912 has been confirmed (in each case by interview, then by checking with one or more of the others who were supposed to be there) were Patton, Willie Brown and his wife - who also played, Tommy Johnson, his brother LeDell, LeDell's wife Marry Bell Johnson, Roebuck Staples of the famous gospel singing family ‘The Staples Singers’, ‘Howlin' Wolf’ (real name Chester Burnett, who admits to having taken lessons from Patton, and still imitates his vocal style, unsuccessfully), Dick Bankston, ‘Cap’ Holmes and a few others who evidently travelled through the area from time to time but whose presence cannot be confirmed due to contradictory information.

According to Sam Chatmon, Patton already played and sang ‘just like’ the older brothers and sisters of the Chatmon family before he came anywhere near Drew. And since Patton seems to have left Drew still singing and playing in much the same way as before, it may be supposed that he was a major, if not the major influence on the Drew scene. Undoubtedly he left with more than he had come with - such atypical Patton songs as Frankie And Albert and Some These Days I'll Be Gone, for instance - but it seems probable that Tommy Johnson, Willie Brown and others learned much more from Patton than he did from them; this has been admitted by Howlin' Wolf and Roebuck Staples. Some confusion exists as to who learned what from whom, in the case of Tommy Johnson, since Patton's first home was very near Crystal Springs, where Johnson was born. For example, both men recorded versions of Pony Blues, for the same company, less than a year apart. Both played in open G, ‘Spanish tuning’; and not only did they both use the same tune contour - which might have been expected - but Johnson in his treatment (Paramount 13000, Black Mare Blues), used virtually the same tune phrases as Patton employed on Pony Blues. Both men used to clown; Patton danced round his guitar, Johnson round and on his Gibson. On the other hand, Patton never recorded anything in the standard tuning, key of D; and this was a tuning much favoured by Tommy Johnson, as well as by other musicians who played round Jackson a good deal, such as Tommy McClennan, the Bullfrog Blues Man. There are certain songs and verse complexes which are associated with the key of D, such as those found in the many variants of Big Road Blues - which Sam Chatmon recorded with the Sheiks, under the title of Stop And Listen Blues. The significance of all these musicians living in the same area at the same time lies in three facts. First, there was a great deal of communal creation. Secondly, after these people left Drew, the songs, lyrics, styles and so forth, which they had learned and created there, began to appear in the north (as far as Chicago and Detroit, up to the present time) and the rest of the south. They may still be recovered by any field worker virtually anywhere in the United States where there are performing, non-professional black musicians - even in the western states. (This claim takes no account of instances where the singer has learned the song from a phonograph record, even though some folklorists consider records as merely an extension of the 'normal' person-to-person diffusion process.) Thirdly, these songs, styles and lyrics became known as 'blues' even though performances, and recordings of performances, by city groups had previously been and continued to be called 'blues'. The 'city blues' were generally performed by groups, with quite 'regular' metric structure and textual coherence. These evidently newer 'country blues' were more individual (and perhaps more personal), irregular and textually incoherent or ambivalent.

Certain differences in performance can be described between those singers who went north and those who remained south, but the similarities are much greater. If field recordings and commercially issued phonograph records from the north contain more vocal growling and are delivered more harshly than those from the south, if very few examples from the north exhibit guitar-playing in the key of D while those from the south do, then source-analysis usually indicates that in the north many singers learned their songs and styles, directly or indirectly, from, say, Patton, while those in the south learned theirs from Tommy Johnson.

Musicians from the north were also, to a great extent, influenced by the Son House, Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters group; those in the south by singers from Bentonia, Mississippi - Skip James and his friends - another instance of communal creation.

In many cases, after 1940, and even before that, source analysis indicates that singers learned their songs directly from phonograph records by Patton, Johnson or others. This, I think, represents a gradual breakdown in oral tradition. To attempt to represent the process of learning how to play a song directly from a phonograph record as merely an extension of oral tradition is ludicrous. To attempt to put forth definitive distinctions between a northern and a southern style of singing with the meagre information we have (meagre in comparison with what we need to do so, and could have, had more research been done at least before I940), information gained primarily from phonograph records issued after 1940, would at this late date be ill-advised.

A few years after Patton's arrival, a black soldier returned from the war in Europe and shot a white man in, or near, Drew. Other musicians had already moved, but this event really began the Drew diaspora. Most of the blacks in the area were forced to move.

Brown, Staples and his family, and Howlin' Wolf left and went north, carrying their music with them. Wolf still sings many Patton songs and Roebuck Staples plays like Patton and Brown. The Johnsons moved to the Jackson area; Tommy recorded for both Victor and Paramount a few years later, in 1928 and 1930 respectively, and stayed in Crystal Springs until his death in the 'fifties.

Patton and Johnson appear, in retrospect, to have been more imitated than innovative; more cooperative than creative. Yet few people realise that Patton was part of a large exchange process which went on for several years before his emergence as a prodigious recording star and purveyor of local songs. While Tommy Johnson remained in, or for the most part near Jackson, Patton travelled around a great deal, but chiefly within the confines of the 'Delta'.

Patton later stayed at Dockery's until 1924, at which time he left and in Merigold met Minnie Franklin, whom he 'married'. This woman is still alive. Her full name is Minnie Franklin Washington, and she lives in Bovina, Mississippi. She reports that Patton was singing Pony Blues when she met him in 1924, but the song was probably much older. In Merigold, Patton became acquainted with two sheriffs, Mr Day and Tom Rushen, and a Mr Halloway who made whisky. Patton composed a song about these people called Tom Rushen Blues which he later recorded for Paramount, and High Sheriff Blues which he recorded in New York at his last session in 1934. Patton left Merigold in about 1929 (alone) and met Mr Henry C. Spiers of Jackson, Mississippi. Spiers owned a music store in Jackson, and had acted for years as a talent scout for several large record companies. He sent Patton to the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana, where on 14 June Patton had his first session for the Paramount Company. (Paramount frequently used the Gennett studios.) Patton spent his remaining years performing in the Yazoo Delta in various towns, usually near the Mississippi River, in Mississippi and Arkansas. He rarely left this area to perform.

Patton probably met Bertha Lee Pate (whom he 'married') in Lula, Mississippi, and Henry Sims (a fiddle player from Farrell) in 1929, shortly after his first recording session. He is reported by Son House to have lived and performed at Lula and at most of the local towns, especially on the plantation of Mr Joe Kirby, where he performed with Son House and Willie Brown. He also lived near there on the plantation of a Mr Geffery. He recorded again for Paramount at the company's own studios in Grafton, Wisconsin, in November and December of 1929, taking Henry Sims with him.

He began acting as subsidiary talent scout for Spiers shortly after his first two records were issued. It was through Patton that Willie Brown and Son House were recorded. In May 1930 he went to Grafton with House, Willie Brown, Louise Johnson (who sang blues and played the piano) and Wheeler Ford of the famous 'Delta Big Four' gospel quartet. Patton's final Paramount session took place on 28 May. According to Son House, Paramount used two microphones, one for voice and one for instrument. Skip James said the same thing except that when he played the piano, the recording engineer also put a microphone on his feet. The artists were well 'lickered up' before recordings were made.

Shortly after this, Patton and Bertha Lee lived for a while in Cleveland, Mississippi. It was here that Bertha Lee is reported to have had a fight with Patton and to have cut his throat with a butcher's knife. She, of course, will not discuss the matter, but the story is well known in Cleveland. That Patton survived, but with a scar on his throat, and, nevertheless, stayed with Bertha Lee is well established.

In 1933, Patton and Bertha Lee moved to Holly Ridge, where they performed locally together. Patton was suffering greatly at this time, and prior to it, from a heart ailment of which he was soon to die. He was chronically out of breath and it would take him two or three days to recuperate from a night's singing.

In early January of 1934 an 'A&R man', Mr W. R. Calaway of the American Record Company (ARC) went to Jackson in search of Patton. A&R stands for 'Artists and Repertoire'. A&R men work for record companies and music publishers; they select artists for certain songs which they want to get recorded and help supervise the recording sessions. W. R. Calaway performed both functions with such white, 'country' entertainers as Roy Acuff, Bill and Cliff Carlisle, and others. With Patton and Bertha Lee, he probably performed only the latter function. Calaway later tried to get Willie Brown and Son House to record for him, both of whom refused for different reasons. He wanted to take Patton to New York to record for his company. He contacted Spiers and asked him for Patton's address, but Spiers refused to give it to him, because, he claims, Calaway had swindled him in a previous business deal. (Spiers recalls this vividly. Unfortunately, Calaway could not be consulted, since he died in Orlando, Florida in about 1955.) Spiers notwithstanding, Calaway found Patton and Bertha Lee in Belzoni, Mississippi. During the evening of the day Calaway arrived, Patton, Lee, and others were jailed because of a commotion that had occurred in the roadhouse in which they were playing. Mr Purvis, the 'High Sheriff' of Humphreys County, and Mr Webb, his deputy, were the local law-enforcement officers. Calaway later bailed out Patton and Bertha Lee and the three left together for New York. Patton sings about both law-enforcement officers on High Sheriff Blues. Patton's (and Bertha Lee's) last recording session took place on 30 and 31 January, and I February 1934. At this session Patton sang as the last verse of his 34 Blues:

It may bring sorrow, Lord, and it may bring tears, (twice)

Oh, Lord, oh, Lord, let me see your brand new year.

He never did. The ailment which had bothered him for years was to put an end to his life. Shortly after he returned to Holly Ridge from his ARC session, he became ill. He was taken to a hospital in Indianola, Mississippi, on 17 April 1934, released 20 April, and died 28 April. Mississippi State Board of Health Certificate of Death Number 6643 attributes the cause of Patton's death to 'Mitral Valve heart hose' (heart failure).

When fully grown, Patton was quite short, about 5 ft 6 inches tall, and of lean build. He had light skin and Caucasian features. He is reported to have played practically everywhere in the Yazoo Basin and to have travelled with medicine shows. During many performances, as stated, Patton did tricks with his guitar, such as dancing around it, banging on it while he played, and playing it behind his head. He taught Howlin' Wolf, Willie Brown, and Son House a great deal on the guitar.

As distinct from such travelling performers as Blind Lemon, Blind Blake, Lonnie Johnson, and others, Patton spent almost his entire life in or near his native Mississippi Delta. He left it rarely to perform, and only a few times to make records. His recorded repertoire reflects his limited picture of the world. When he does mention place names, such places are usually located in the Yazoo Basin. Here is a list of place names Patton mentions, with the corresponding master numbers:

15220 Memphis, Minglewood (in Memphis).

15221 Pea Vine (name for either any branch line of a railroad or in this case the branch line of the Southern Railroad, which ran from Clarksdale through Shelby, Merigold and other small towns, to Greenville).

15223 Parchman (the Mississippi county farm for Negroes).

L-44 Marion, Arkansas and the Green River. (The Green River is not on any map but is a local name for a small river in the Delta near Dubs.) The Southern Railroad and the 'Yellow Dog' Railroad, a local name for the Yazoo Delta Railroad.

15214 Natchez, Jackson.

L-432 Clarksdale, Sunflower; Helena, Arkansas.

15223 Hot Springs, Arkansas.

L-37 Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana (occur as part of a refrain, probably traditional).

L-38 New Orleans (occurs in a verse of a traditional blues-ballad).

L-41 Louisiana.

L-59 Sumner, Greenville, Leland, Rosedale, Vicksburg, Stovall, Tallahatchie River, Jackson; Blytheville, Arkansas.

L-63 Gulf of Mexico; Vicksburg; Louisiana; Shelby, Illinois (not on any map).

L-77 Chicago.

L-429 Lula.

14725 Belzoni.

14727 Vicksburg, Lula, Natchez, Greenville.

14747 Mississippi, Dago Hill (a local name for the region north of Mound Bayou, Mississippi: a great many Italians live there).

Only the following people are mentioned:

15222 Tom Rushen, Hollaway, Mr Day.

14725 Mr Purvis, Mr Webb.

14739 Hollaway, Will Dockery.

14757 Bertha Lee.

No person of more than local prominence is ever mentioned and no one from outside the state of Mississippi is mentioned. When Patton sings of external events, he usually refers to local ones: the 1927 flood of the Mississippi River (Paramount 12909, High Water Everywhere - Parts I and 2), the drought of the following two years and how it was felt in Lula (Paramount 13070, Dry Well Blues), the demise of the Clarksdale Mill (Paramount 13014, Moon Going Down). The one exception is his description of the 'Railroad strike in Chicago' (Paramount 12953, Mean Black Moan).

Patton was dependent upon, and a product of, the prevailing socio-economic conditions of the southern cotton production economy, a semi-feudal society. According to Son House, Sam Chatmon and others, he detested and avoided manual labour and spent most of his adult years as a semi-professional, paid (or kept) entertainer. There was room in this economy for a few full-time professional entertainers, and although the entertainer did not earn a sumptuous living, he made a decent one relative to the standards of the time and place. If he was supported by numerous roadhouses and corn-liquor salesmen, these roadhouses and bootleggers in turn were dependent upon the (sometimes) wealthy plantation owners. Most Delta blacks worked for the plantation owners and were paid but meagre monetary wages. There was a great deal of restriction of personal freedom, and many blacks led lives similar to those of medieval serfs. Everything was white-owned and the law of the land was white law.

On the other hand, blacks who worked on Delta plantations were always provided with housing (called 'quarters') and frequently with food. When the depression came and there was no work, the black workers were fed by the plantation owners, protected by the benevolent southern land-owner tradition. There were few jobs in the Delta for blacks that did not deal with cotton, and they could not rise to a very prominent position even among their own people. A black man could become a preacher, but the best he could do in secular life was become an overseer (the leader of a cotton crew) or a musician.

If we search Patton's lyrics for words expressive of profound sentiments directly caused by this particular cotton-economy, or for words expressing a desire to transcend this way of life, if we search for verses of great cultural significance depicting any historical trend or movement, or aspirations to 'improve the lot of a people', we search in vain. Such a search would not be fruitful with any blues-singers. Patton could, of course, only sing about his own limited experience. He had a very narrow view of the world. And there was perhaps no intellectual climate available to Patton for the development of significant thoughts or comments about his and his people's status.

Patton was an entertainer, not a social prophet in any sense. He had no profound message and was probably not very observant of the troubles of his own people. He was not a 'noble savage'. Least of all did he try to express the 'aspirations of a folk'. His lyrics are totally devoid of any protesting sentiments attacking the social or racial status quo. In fact, according to Son House, Patton had very good relations with white people, many of whom helped to support him in return for his services. They liked not only his folksongs but also his blues. Both Patton and House were frequently received into white homes, slept in them, and ate in them. The racial segregation of Patton's day was not as rigorous as it is now, and it was not as insidious.

Beyond mentioning place names, Patton's lyrics have nothing distinctively regional about them that could have made them products of only a particular time and place. They could have been produced by any songster from any agricultural-economy region of the South. Most of his lyrics, or portions of them, are probably floating verses derived from field-hollers and other sources. As such they could have been performed or recombined, as they were, by anyone familiar with the tradition. It is impossible to determine exactly where and when such verses were composed, as it is impossible to reconstruct an authoritative history of black music in general. No one was interested enough at the time to survey what was happening.

As has been implied, the function which Charley Patton performed in his society was, for the most part, that of an entertainer. His function as a musician was subordinate. Patton used his musical abilities, as well as his ability to dance and to do tricks with the guitar, in order to please an audience.

We cannot know, of course, what Patton did when he was alone. Perhaps, while entertaining himself (assuming that he did so), he concentrated more on his musicianship. But as star performer of a medicine show, as the source of music for a dance, as roadhouse entertainer, as paid background music for back-country gatherings whenever local corn-liquor salesmen set up shop, Patton's job was to help everyone to enjoy himself.

Son House and Ishmon Bracey both commented on Patton's clowning. House did not approve of it and is to this day critical of Patton. As a result, when some of Patton's recordings were played for House in 1965, he was amazed at Patton's technical proficiency. 'I never knew he could play that good', he said. He then explained that while Patton was apparently a great musician, the purely musical aspect of his public performances suffered as a result of his 'clowning around', which House insists Patton preferred to do.

The apparent selectivity of House's memory seems strange in view of the fact that House was present while Patton made some of the same records which were played for him 35 years later. But House had simply forgotten that Patton was a competent musician because he saw him so frequently as an entertainer and so rarely as a serious musician. Vocal and instrumental proficiency were necessary for an entertainer, but they were not enough. Patton had the other talents as well. What we hear, then, on Patton's records is apparently not the way Patton sounded in public. On records we hear him consciously trying to be a good musician. But we should not make too much of the probable differences of performance in the two situations. Patton could not have suddenly summoned up so much technical proficiency at the recording sessions if he did not already possess it. Thus, there were probably other times when Patton performed primarily as a serious musician. Unfortunately, no one remembers such times. Perhaps he performed seriously only when he was alone. If Patton's recordings are of Patton at his musical best and do not sound exactly as he sounded at public performances, there is no reason to suppose that what he played (music and text) varied in the two situations. Thus, it seems safe to conclude that Patton's recordings constitute a valuable and accurate sample of what Patton was playing and singing during the last years of his life and probably for many of his earlier years. It should be remembered, for example, that he was performing some version of his Pony Blues as early as 1924, five years before his first recording session.

Excerpt: Charley Patton by John Fahey

Published: 1970

Publisher: Studio Vista

Country: UK

Thursday, 15 August 2013

Jimmy Yancey EP - Vogue EPV 1203

Back Cover Notes

In various fields of music there tends to be a period when simplicity is shunned in favour of a complexity which sometimes covers up a lack of basic content. We are in such a period at the present time as far as jazz is concerned and for this reason the piano work of Jimmy Yancey is known only to a few collectors. Yet, Yancey has influenced the field of blues piano playing to a considerable extent and better known pianists like Meade Lux Lewis have frequently paid tribute to him.

Yancey was born in Chicago in 1894 and in his twenties he toured Europe as a dancer and singer. For thirty years he was employed as a groundskeeper at a Chicago baseball park and only played the piano at rent parties and private functions. His wife, Estelle Yancey, is a blues singer of great talent and she recorded with him on a number of occasions. Yancey died in Chicago on September 17, 1951, leaving behind him only a few records.

From all accounts, Yancey was a quiet, gentle man and this is shown in his playing. His style was one of stark simplicity and he used a number of themes often retitling them, and created innumerable variations within this framework. In one sense Yancey was a technically limited performer, but such is the impact of his work that this is never obtrusive. The four sides on this record were originally recorded for the American Session label in December of 1943 and are amongst Yancey's most moving work. At The Window is a particularly reflective solo and has a characteristic haunting beauty. The Rocks is a very familiar Yancey theme and is superbly played here. In fact, all the four numbers on this record are outstanding. There are very few records issued at the present which really qualify as great, critical assertions to the contrary, but this is, in my opinion, one of them. The very simplicity of Yancey's playing is deceptive, for it is not the simplicity of an inadequate performer. Within his self-imposed framework, Yancey created music that, by its moving quality and absolute authenticity, deserves to rate as a classic of its kind. Those who fail to perceive the validity of this music reveal only a formidable lack of sensitivity.

Albert J. McCarthy

Vinyl Details:

Label: Vogue EPV 1203

Country: UK

Released: 1957

Genre: Boogie-woogie

Side 1:

01 At The Window

02 Boodlin'

Side 2:

01 Sweet Patootie

02 The Rocks

Thursday, 25 April 2013

Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia - RFH - 21st November 1999

Programme Notes

Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Rome

A short history

The Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia are based at one of the world's oldest musical institutions. Founded in Rome in 1566 it was formally recognised by Pope Gregory XIII in 1585 when he gave it the title "Congregation of Musicians under the invocation of the Blessed Virgin and of Saints Gregory and Cecilia." Since then such eminent composers and musicians as Palestrina, Paganini, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Respighi, Nono and Berio have been associated with the Academy.

On 2 February 1895 the Academic Hall of the Via dei Greci was officially inaugurated and thirteen years later, in 1908, the Orchestra of the Academy gave its first concert. The Chorus, 90-strong, and the Orchestra have given an estimated 13,000 concerts in their history and, at home - with concerts in the Augusteo (built in the ruins of Augustus' Mausoleum) and the Auditorio Pio di Roma (situated near St.Peter's Basilica) - they have a regular audience of between 20,000 and 25,000 people, including 7,000 subscribers.

The list of distinguished conductors is headed by the Orchestra's Principal Conductors: Bernardino Molinari, Franco Ferrara, Fernando Previtali, Igor Markevitch, Thomas Schippers, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Daniele Gatti and, currently, Myung Whun Chung. In addition, between 1983 and 1990, Leonard Bernstein was the Orchestra's Honorary President. Other conductors have included a number of the most famous composers of the 20th Century - Gustav Mahler, Claude Debussy, Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith - as well as such legendary conducting names as Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Victor De Sabata and Herbert von Karajan.

The Orchestra was the first Italian orchestra ever to appear at the BBC Henry Wood Proms in 1995, just one of its many concerts in a busy touring schedule which has recently included visits to Australia (with Sinopoli), South America (Maazel and Gatti), Russia (Gatti) and - with Maestro Chung - Spain, Portugal, China, Korea and Japan, where they were the resident orchestra at the Pacific Music Festival in 1998.

The Chorus also leads an independent life, and has appeared in many festivals, most often at Spoleto's Festival dei Due Mondi. Others have ranged from Paris's Festival of XX Century in 1952 to the 1987 celebrations of the 750th anniversary of the founding of Berlin. In 1995 the Chorus toured Canada and the United States as well as revisiting Berlin for concert performances of Verdi's Otello with the Berlin Philharmonic under Claudio Abbado.

Together the Orchestra and Chorus have made a number of recordings with such conductors as De Sabata, Solti, Maazel, Schippers, Giulini, Sinopoli, Bernstein (including Puccini's La bohème), Gatti and, most recently, with Chung. Their recordings of Fauré's Requiem for Deutsche Grammophon with Cecilia Bartoli and Bryn Terfel won a prestigious "Diapason d'Or" and other recent projects with Chung have included a Beethoven disc and a programme of sacred music in honour of the 2,000th anniversary of the birth of Christ.

Wednesday, 17 April 2013

Henry Red Allen - Jazz Monthly - February 1970

During the late Henry Allen's last but one trip to this country I spent many days with him while he taped his autobiography. It was originally intended that it should be published in book form by Cassell & Company Ltd., but for a variety of reasons the plan has had to be dropped. On his final British trip I proposed to get Henry to fill in and enlarge certain parts of the autobiography, but an initial meeting convinced me that his health was such as to make this impossible. In fact he died within a couple of months of concluding this tour which, I am certain, was undertaken only because medical expenses had taken most if not all of his savings. The autobiography was to be called, at Henry Allen's request Make Them Happy, and Henry was particularly keen to correct what he felt were false impressions of early New Orleans days. This extract, and others that will follow, deal in the main with New Orleans and the musicians with whom Henry Allen played there. I have, as far as is possible, kept the story exactly as Henry told it, only making minor corrections in a few instances, though the order of telling has been slightly readjusted to follow a chronological sequence. I first met Henry Allen in 1958 and in the ensuing years my respect for him as a man and as a musician grew at each meeting, so that when I heard of his death I was conscious of the loss of someone whom I had come to regard as a personal friend - a feeling shared by many who knew him in this country. I am happy that extracts from his story can appear in Jazz Monthly and am grateful to Dr. Desmond Flower and Mr. David Polley of Cassell & Company Ltd., for their co-operation in making this possible.

Albert McCarthy

The Early Years - Henry 'Red' Allen

As far back as I can remember I was playing music, starting in my father's band when I was about eight years old. The band consisted of eleven pieces as a rule - three trumpets, two trombones, alto horn, baritone horn, two clarinets, and bass and snare drums - and I played either trumpet or alto horn. My other job with the band at this time was to carry the music, as frequently my father cut off the titles of the more popular pieces to avoid other bands copying them, and they were just called out as number one, number two, and so on. My mother stopped me playing the trumpet for a while, on account of the fact that she had seen some of the great musicians of the day with their cheeks puffed out and their necks protruding and reckoned the instrument was too strenuous for me! She told me to play an easier instrument and got me a violin, but though I took a few lessons from Peter Bocage I was never keen on it and the practice came to an end one day when a friend visited our house and found me playing it like a bass fiddle. Just as I was about to make some excuse my father yelled at me and asked what I was doing playing the violin that way. I couldn't figure out how he knew but discovered that he had a mirror in his room and by looking into it could see what I was doing. After this I got back to practising on the trumpet again, though my father tried hiding it or turning the valves to keep me from blowing, not because he was really against my playing it but because he was trying to please my mother.

By day my father worked as a longshoreman and at this time most musicians had day jobs away from music. His band had probably more great musicians in it than any other I have heard of, such guys as Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Big Eye Louis Nelson and many others I could name, and this was great for me though at the time and for many years afterwards I had no idea that they would be recognised as pioneers or makers of jazz history. By now I was playing trumpet pretty well, my father having convinced my mother that it could be done without my having my cheeks puffed out or my neck protruding! I kept getting compliments from neighbours about my playing too and I think that my mother rather went for this.

Those parade jobs with my father meant a lot of walking. At first he would arrange for me to meet the band at some corner and then I could come in and play a number, generally getting a lot of applause, though whether for being good or just because I was a youngster is something I don't know. After a while I went all the way in the parades, walking miles and miles, and I just grew up in this setting. At one time Louis Armstrong and I happened to be in my father's band, on a parade - I just realise now what a brass section that could have been with Louis, my father, and myself - and already Louis was great and because he squeezed me I played as well as I could. My father wasn't a great jazzman but he had lots of power and was a fine musician as far as reading and organising was concerned, in addition to being an outstanding conductor. He brought a lot of guys into New Orleans from such places as Tipita and Morgan City, and at one time had two brothers of his in the band, Sam and George Allen. I've seen several early New Orleans photographs of parade bands where the drummer is listed as unknown, but it was my uncle, George Allen. We also had an uncle in Burbeck City, which is across the river from Morgan City, same as Algiers and New Orleans, by the name of Ezekiel Mack, and though I never did hear him personally I was told he could play well. Then, on my mother's side, an aunt of mine was a very fine organist and pianist who used to play in the church a lot. That gave me the chance to play in the church as well, on such numbers as What a friend we have in Jesus. That was my crip at that time - when I say crip, I mean my outstanding number.

Nowadays lots of people ask me about Louis, and as I remember they had a lot of great trumpeters around New Orleans but Louis was already coming up to top them all when I was a boy, though at the time I didn't pay too much attention - like, if I was to live this over, I'd have the same life again but would pay more attention to what was going on. Still, Louis was really great then, along with Buddy Petit and Henry Rene, and I admired, Louis, Rene and Chris Kelly, though I never did go for playing with the plunger myself like Chris, learning how to growl without one.

Most of the bands at this time played spirituals, because they believe in sadness at birth and rejoicing at death. That's why they went in for big parties when someone was dead, and everybody would have a band for a funeral, it didn't matter whether they were poor or had a lot of money or belonged to a lot of clubs and societies. If you belonged to four or five societies or clubs, you had four or five bands. If you didn't belong to any, they would put a saucer on your chest - the deceased's chest that is - and others would walk into view the body and contribute five, ten, fifteen or twenty cents, or a quarter, whatever could be spared. Now whatever was raised, you got a band to coincide with this, musicians getting three dollars for a parade and the leader four dollars, the extra dollar being for phone calls, or if the band already had a gig on the same day then the dollar was clear. Talking of phone calls, it wasn't like it was today then, for the number of people with phones in New Orleans was not all that great and the lines seemed to be always open so you could talk as long as you wanted for a nickel. My father always gave the number of our local grocery store where the owner, a very kind guy, would call anyone to the phone that was wanted. If a call came through for my father he would go to the front of the shop and holler his name, then neighbours would shout from house to house until it reached us. Maybe then my father would have to get dressed properly to go and take the call, but nobody ever seemed to mind waiting and it was still all done for a nickel! Usually calls were about jobs and I would go along with my father to get the men for a funeral or parade or whatever it was, and if it was during the carnival days or Mardi Gras there would be a shortage of available men and my father would be foraging about in the places out in the country, picking up musicians like Punch Miller or Papa Celestin to fill in...

Sometimes during a funeral we would go into the church - the band that is - and play these different hymns. That's where I would come in as the watchman, for the band would then go over to a bar while I would lie on the ground or sit outside until the people are coming out of the service. Now, when I got that cue, I would dash over the bar and call the guys. The snare-drum player would be the first one I'd call, he'd then make a roll and he's rolling until everyone comes out of the bar. When everybody's there the bass drummer would hit three notes, I mean three beats - no cymbal, very slow. As a matter of fact, they're organising what number they will play, and they go into that number. Then the snare drummer takes off the snares - they give a kind of tim-tom effect - and that's where the sadness came out, with people probably crying or screaming. Now it's a slow walk to the cemetery and when you get there - from a kid up, I done this - the sermon going on and, when they say "Ashes to ashes, dust to dust" or whatever goes on, well the drum gives a roll again from outside the cemetery, and they're ready to come back again, and the band plays that first number "Didn't he ramble, he rambled till the butchers cut him down". After that, everybody's having a ball, parading back in tempo, the band playing different numbers. That's when my dad used to say "Take it, son", that's where I would come on and play the jazz numbers.

We didn't go straight into the hall as soon as we got back - people would be jumping in the streets and everything - and if they have two or three bands they're going into a buck, by 'buck' I mean a session when the bands play against each other. When the bands got back home they might at first make for their hall but they'd never go straight in, you'd first go across the street, to the corner, come back around and then go into the hall. But you then came back and played for ten or fifteen minutes out there on the porch, which we called the gallery. Now, if you're a member of a club, you'd get a dollar for carrying the banner, fifty cents for carrying the flag, and it's up to you to give the two guys something that's holding the tassels on each side of the banner. Sometimes a musician had to double from playing at this funeral or parade to go and work at a dance the same night - I'm sure that's one reason why the guys had such strong embouchures around New Orleans. Now the job that night, wherever you're playing, that calls for a meal - all contracts call for a meal during the time of the dance, and also state that you must be paid for the job right after the dinner or the supper you're having. And you'd probably have gumbo or ham and potato salad, you could get either one, one to each musician. But I liked playing with Chris Kelly because he was a little superstitious, he didn't eat anybody's food but what he brought with him you know. So that would give me two chances, and I would make sure I got Chris's share, having gumbo and a ham and salad. When I say Chris was superstitious, I mean that he always had the feeling that somebody would poison him or do him wrong, so always brought his own meals.

I read a statement in a book, I think it was Nick La Rocca's book, that he was one of the originators of jazz. Well, who can say who was the originator of this? Anyway, he mentioned that when he went to Chicago, the recording people went on trips to New Orleans to find somebody who could play jazz and couldn't find them. I resent this remark very much. Although I have nothing against what he played, or what anybody plays, as far as that, we certainly had a lot of people around New Orleans at that time who could play good jazz and I guess that they could not have looked very hard, or maybe they were looking just one way racewise, whether they went uptown, downtown, back o'town or what. Whether white or coloured people started all this I really don't know - it was started before my time - but the coloured people must have had something to do with it.

I remember hearing a little boogie-woogie, but we didn't have too many pianists in New Orleans who were well known at this time. Instead of using piano we generally used a guitar, and I think the reason for this was that everybody had a piano in their home, whether they played it or not, my guess being that as many as 90% of the houses had one. Guys like Clarence Williams used to plug numbers from door to door; he'd come into your home and play your piano, and sell his numbers - the price would be around ten cents whatever the number was - then he'd go next door and play again, and so on. In addition every saloon or tavern had a piano in it and you were free to go in there and bang on the piano, whether you could play it or not. So a guy taught himself, but they didn't learn within the boogie idiom or anything like that, because they thought they would have to play along with a band. We did have a few boogie woogie players but they weren't all that many in number. Another big reason why few of the bands used a piano was that most of the halls, the dance halls rather, didn't have one, so you'd need to borrow a piano from someone's home in order to use it. Now it was easy to get thirty or forty guys to help you take this piano out of these people's home up to the hall, but where people stopped loaning the piano out, it was getting it back. After the dance they had trouble in getting anyone to haul it back. To get back to the parades again: The uniform for parades was white pants, blue shirts. Naturally the hats were reversible, you could take the top off and leave the white on, but when we played a funeral we wore dark suits to mark the sadness of the occasion. My father used to give dances to collect enough money to get the uniforms, and you can see in some of the old photographs the musicians with the uniforms on, including my father with the great hat that had all the trimmings on. When they had these great dances I would be there all night, now and then nodding off for a few minutes, but going straight on to school next morning. My father was very strict about that and made sure that I went to school always, and I did pretty well there at Macdonnel 32 which is in Algiers, that's on the west New Orleans side, so not being a drop-out I made it through to High School before the trumpet finally took over completely.

They had a lot of great parade bands in New Orleans when I was a kid, some of them still going today incidentally, such as the Onward, the Tuxedo, and the Excelsior. As a matter of fact I played so regularly with the Excelsior Band that some people must have thought I was a full time member, starting out by playing the drums - either bass drum or snare drum - and managing to get a few good gigs as a result. When I was a kid I was also a very fine - though I say it myself - ukulele player, having good wrists and the ability to pick up chords very quickly. After a while there were so many good ukulele players around that I gave up and concentrated solely on the trumpet.

The first time I played one of the dancing schools - where the band never stops and goes right on through - I was on parade and a very fine bass man by the name of Doug Ernest offered me a job that night. So I got in touch with my father and went right on and played that job after he gave me permission to take it. There was a guy in the band, a very fine trombonist by the name of Freddie Bubu, who admired me and he told me that he thought I played like Louis. Anyway, we played all that night; only thing was these guys, every one of them, was getting a drink of water now and then, and I didn't know what was happening. I was trying to play right on through, but that was supposed to be the rest period, something that I didn't understand.

Looking back on the jobs I played in New Orleans away from my father's band I remember working at a couple of halls, one was called the Young Friends Of Honour - we called it the Turtleback - and another was the Sacred Heart. I also played at the Eagle's Hall which was at the end of Algiers at a place called McDonoughville, then at a few places around Gretna, all of them being within about a three-mile radius of home. One time I remember getting caught up in a jam session with Kid Thomas and our group were supposed to have won the contest, anyway they gave us the prize which was a sachet bag. The people at the hall didn't seem to like this too much and on the ground that we were kids they had some policeman come and take the bag back and it was then given to the Kid Thomas group. We couldn't do anything about it because we had no business in the place in any case, on account of our age. Soon after this I ran into George Lewis and my father gave George permission to use me on a job. The very first night I played with George someone fired off a pistol in the place we were working and the police raided it, as a result of which the whole band were taken down to the station. Fortunately they didn't keep us in prison long and released the whole band. Another time I played with Willie Cornish, a great trombone player at that time, and he used the kids band for a job in a cabaret where they used to keep the whiskey in the basin - what we called a face basin in which you washed - in case the police came in. If they did arrive all they had to do was to tilt the basin and waste the whiskey, and no evidence! If someone offered us a drink we would have a coca-cola and whoever offered it to us had to pay the price of a whiskey to the cabaret owners, though this was alright by me as I wasn't drinking anyway.

One of the greatest of the trumpeters in New Orleans around this time was Emmanuel Perez, and I had the great fortune of working with him. As a matter of fact I worked with most of the guys around there on various jobs but the two men who took the most interest in me were both trombonists, Yank Johnson and Harrison Barnes. It was Yank who got me a job with the famous Sam Morgan band, though I was just used as an extra with each guy giving me a dollar apiece or maybe fifty cents, just what they felt like giving. The Morgan band usually worked at a place called the Astoria Ballroom and I remember that Sam Morgan had been taken ill and so Yank Johnson had brought me along to fill in for him. Meanwhile the other members of the band had sent for Henry Rena to take Morgan's place and that's how I became the extra, though I must admit that this job was one of the greatest kicks of my life, for I could enjoy listening to Rena without having to be on a parade. The band had just got hold of a number called Weary blues, so they passed around the sheet music for this and quite naturally everybody wanted to show their musicianship and didn't want to be seen peeping at the music too closely; they wanted to show off to the public and prove themselves to be fast sight readers. In fact, though, the Morgan band had already run it down a few times in private rehearsals, but Rena had trouble getting into it until Yank nudged him on the leg and told him that it was the same thing as Shake it and break it. Once Rena realised what it was he really went into it.

My first trip away from New Orleans was a job with the Sidney Desvigne band on the "Island Queen" which went as far as Cairo and then back again. We had such guys in the band as Bill Matthews, trombone, "Pops" Foster and Walter Pichon who was one of my ace boys, we had done a lot together since our school days. On the boat Pichon became a very good player of the calliope. It was when I got back from this trip that I heard from King Oliver.

Quite a few people I knew had left New Orleans to play with Oliver - Barney Bigard, Albert Nicholas, Paul Barbarin and Luis Russell amongst them - but then some of the men dropped out of his band and he sent home for Willie Foster, Paul Barnes and myself. We left together and joined the band in St.Louis in April 1927. I have read in some articles that I joined the Oliver band in Chicago but I didn't get there until some time after this. I could never understand why they use terms like "Chicago Jazz", "New Orleans Jazz" or "New York Jazz", because I made records with the Chicago Rhythm Kings before I had ever been there. Anyway I met the Oliver band in St.Louis and it was a great experience for me, but nothing to what I felt when we arrived in New York and saw the banners there running from one side of the street to the other, with a sign saying "The East Meets The West". We played against, or rather alongside, Fletcher Henderson's band and the Fess Williams band, and in the latter group I had the pleasure of hearing Jimmy Harrison for the first time.

After a while the guys in the band got a little nervous at facing the top bands in New York and went to talk to King Oliver, Oliver reassured everyone by pointing out "We're playing what we know" and as a result we began to gain in confidence. We had some great musicians in the band and they included Omer Simeon, Barney Bigard and Paul Barnes in the reed section. Tick Gray - a very good trumpet man who is not too well known - along with King and myself made up the trumpet section, and there was Kid Ory on trombone, Paul Barbarin and Willie Foster - "Pop" Foster's brother - in the rhythm section. I stayed a little while with Oliver and we worked at the Savoy Ballroom, though as a matter of fact I was not too keen on being away from home because I was used to my mother doing everything like seeing to my clothes and getting all my meals, and didn't like the idea of having to do everything myself. I found it hard to get used to the idea of being away, particularly for any length of time, in these far parts. Fortunately King Oliver took a liking to me and insisted that I lived with him at his sister's place, so one way and another I began to get some confidence. We did pretty well against some of the great bands in New York, but I felt that I wasn't too well established there, particularly in my knee pants! You see at this time it didn't matter what size you were, until you reached a certain age in New Orleans you wore knee pants. I was saved by a guy called Buchanan who rented a suit for me from a rental firm under the Savoy, so I felt pretty great then and began to take more interest in what was going on. When we took the stand we played and everybody gathered around the bandstand to hear what we had to offer, and then the next band would play and after that we were back again, so it was real interesting. Then our gig at the Savoy ended and we were to have gone into the Cotton Club, but something happened there, though to this day I never found out what it was - maybe finance - and Ellington got the job. We were very disappointed at this, for we had been certain of getting the job and had been promised it for sure. Instead we set off to play a dance at Baltimore but we had very poor luck there. Our first dance was completely rained off, so we thought we had better do something to cover ourselves in the future, particularly as our room rent and meal bills were beginning to run up and our landlady was starting to cut down on our meals - King Oliver used to have this bowl of sugar and water along with about half a loaf of bread before he got into his meal - and the boys got a little desperate and tried to get started on their meal before King knew about it. Then King made a deal with the lady to bring him in fifteen or twenty minutes before the meal and serve us all at the same time. But the lady was still a little worried because the loot wasn't coming on, so to make sure we got our loot at the next dance we insured it - if it rained or anything, we'd get paid. So it rained on that day, and the curfew must have been eight o'clock, because it rained right up to eight o'clock and then stopped! That threw us out, made our contract with the insurance no good, and to make matters worse the rain had messed up the light fixtures at the place we were supposed to work. Everyone got discouraged and the first one to leave was Clarence Black, he was a violinist who was fronting the band, and when he got home he formed his own group and sent for Omer Simeon. Most of us went back to New York, still trying to stick around in case any jobs came up and with King Oliver still trying to hold us, but nothing happened and I went on home to New Orleans.

I had not been home long before I got a job with Walter "Fats" Pichon, working at a club called The Pelican about four nights a week, and this worked out very good. There were two bands sharing the job, the one led by "Fats" Pichon and another led by Oscar "Papa" Celestin, and we used to play against each other. Guy Kelly was in Celestin's band and he and I became the drawing cards, with a lot of people coming along to hear us blowing against each other, though Guy and I became very good friends anyway. The funny thing was that my friends and Guy's friends didn't get along too well for some reason, and they felt that there ought to be more saltiness between us just because we were playing against each other, but after a while Guy and I got fed up with this and we decided to go to Chicago together. Guy did go but I had another offer and made up my mind to stick around the home area a little longer, working with Fate Marable on the riverboats.

I'd been listening to Fate Marable since I was small, when I used to go on the levee over in Algiers and the music from his band on the boats would carry across the river. I've already mentioned that I had worked on the "Island Queen" with Sidney Desvigne - this was one of the fleet owned by the Streckfus brothers - and I think that Fate had heard about me as a result of this, for he came into The Pelican one time and after hearing me offered this job. When I started on the boat I got several raises as the Streckfus brothers wanted me to stay on. There were five of them, all brothers, and they were really interested in the music and employed most of the famous early musicians. The other musicians in the band were from St.Louis and included Albert Snaer on trumpet, bassist Al Morgan, and a guitarist called Al Sears - not the tenor player who made his name with Duke Ellington. For a short while Willie Humphreys came in on clarinet, but there were a few changes now and then. We started by playing in and around New Orleans, then we'd leave for a scheduled trip of maybe two months, but usually we'd be gone for three. We didn't dash madly on to St.Louis, but the boat worked its way up, playing night after night in different places. A lot of people think, when you mention riverboats, you had to check your pistols when you came on, and that the boats were full of women good-timing, but I didn't find it like this. I do know that everyone had a good time but it wasn't as wild as some writers say, and I can't remember personally ever seeing any gambling on board when I was playing. We played stops such as Memphis, in fact when we got there we would play two nights, and it was here that a guy called Loren Watson first heard me, or maybe heard of me, because I have the feeling that King Oliver may have mentioned my name to him. We finally would get to St.Louis and play there, and when you reached there it was every tub - that means you have to get off and get you a room outside the city, because the boat would be stationed there a while. We had lots of fun on the boat though, because they had a cook on board who was from New Orleans and I'd suggest that he cook red beans and rice. I found out that he was a great cigar smoker and kept him happy with supplies so he would fix these New Orleans dishes, though the guys in the band who came from St.Louis weren't so keen on rice and always gave us the chance to have our fill!

There were some great musicians out of St.Louis, guys like Charlie Creath, Dewey Jackson and Fate Marable, and as they all played the boats I had heard most of them quite early in New Orleans. One time Creath, Jackson and Marable were all in the same band together, but as they were all leaders in their own right there was some tension going on. I remember once hearing them in a cabaret and when Dewey - a great blues player - ran over his horn to warm it up the people would start screaming. Then Charlie Creath would hit just one note and draw attention - his tone was so big and wide that he would pull everything together - and I thought that both were great trumpeters. When we were berthed in St.Louis I would get around and hear different people, and I remember listening to Johnny "Buggs" Hamilton who later became well known when he played with Fats Waller, and Blue, Reputed Blue as he called himself, who later on was on a couple of my recordings for Victor. His real name was Thornton Blue.

At the time there seemed to me to be so many great players around St.Louis that it's hard to name them all. Others I remember are Nat Storey - a really fine trombonist - drummer Floyd Campbell, and a pianist called Burroughs Lovingood, who as a matter of fact, I still correspond with and is now working in Washington, D.C. Lovingood was a great pianist and we worked together with Fate Marable on the boat, using two pianos. I remember that Fate would get these hard numbers, and play them with just the bass backing him, probably trying to show Lovingood up or something. But Lovingood was a little fast musicianwise, so Fate would study first, hold the music on his lap and run it over a few times, and when pass it out to Lovingood while everybody's looking. And if there was a really hard passage coming up Fate would decide to go and have a drink of water, just when the piano passage was due, and leave Lovingood out there. But he pulled through alright, it always turned out o.k. Fate gave me a message when I left the boat, for Jelly Roll Morton, but I had trouble leaving in any case. You had to put up fifty dollars when you joined the band on the boat - a sort of guarantee of good behaviour - but though you were supposed to get it back when you left I never did have it, still haven't to this day. I went home to New Orleans on account of the fact that my grandfather had passed and I thought, and my family thought, that I should be there for the burial. When I got back after this to the boat they wanted me to stay on, but I had already given in my notice and told them I was going on to New York. They didn't really believe that my story about my grandfather passing was true, claiming I had made it up to get away. First Streckfus ordered me to stay, then he offered me a little more money to remain - I had had raises a couple of times before - and also Fate tried hard to keep me. But I had to go this time, because I had wires from both Luis Russell and Duke Ellington offering me jobs with their band, and was determined to make New York City.

Publication: Jazz Monthly

Issue: 180

Date: February 1970

Country: UK

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+p01.jpg)

+p02.jpg)

+p03.jpg)

+p04.jpg)

+p05.jpg)

+p06.jpg)